A Tool for Group Work

When a class' group work becomes dull, what do you do?

Imagine, it’s Tuesday afternoon. Your class is working on a group project. Students are in groups of 4 and you see that 2 students in a group are excitedly talking to each other about the task. You glance over at the students next to them, eyes gazing around the room. One of them half-heartedly listens to the conversation, while you can see the other start migrating to another group to derail them. Before you know it, there are two groups off task and half of the class is disengaged.

At times, this would’ve been a vignette into some of my classes.

Why Group Work?

My classes have always been centered around some sort of group work. Makerspaces foster a sense of collaboration and creativity that lends itself to positive group work. Students might be working to create a board game that beats indoor recess boredom or creating stop motion animation videos or solving a puzzle involving 4 robots and 8 students. Whatever the project, I tend to put students into groups, not only to create academic scaffolds, but also to hone their cooperative skills.

During my first year of teaching, my school’s Exploratory team focused on increasing group work structures and efficiency. We worked to strengthen students’ P21 Life and Career Skills through a series of department-wide initiatives. Each of our classes would focus on two skills every 6 weeks and rotate throughout the year. For example, every Exploratory class —Drama, Applied Math, Art, Music, Innovation (to name a few)— would all focus on increasing Productivity and Flexibility. We would focus on these skills in the context of group work.

And ever since then, group efficiency has been an object of fascination and research in my teaching practice.

In my 7th year as a makerspace teacher, I’ve conducted effective groups in every grade in K-8 using the same two guidelines:

Groups of 3. It becomes inefficient after 3, unless there are mini-groups made up of 2-3 students.

Clear outlines of group expectations (i.e. pre-determined roles and clearly outlined)

Regardless of project or grade level, these two guidelines have increased student focus and engagement.

Post-It Method

Around year 4, I developed the Post-It method as a tool for student self-accountability. I realized that students might’ve understood what the class goal meant, but they couldn’t (or wouldn’t) translate it to their individual task.

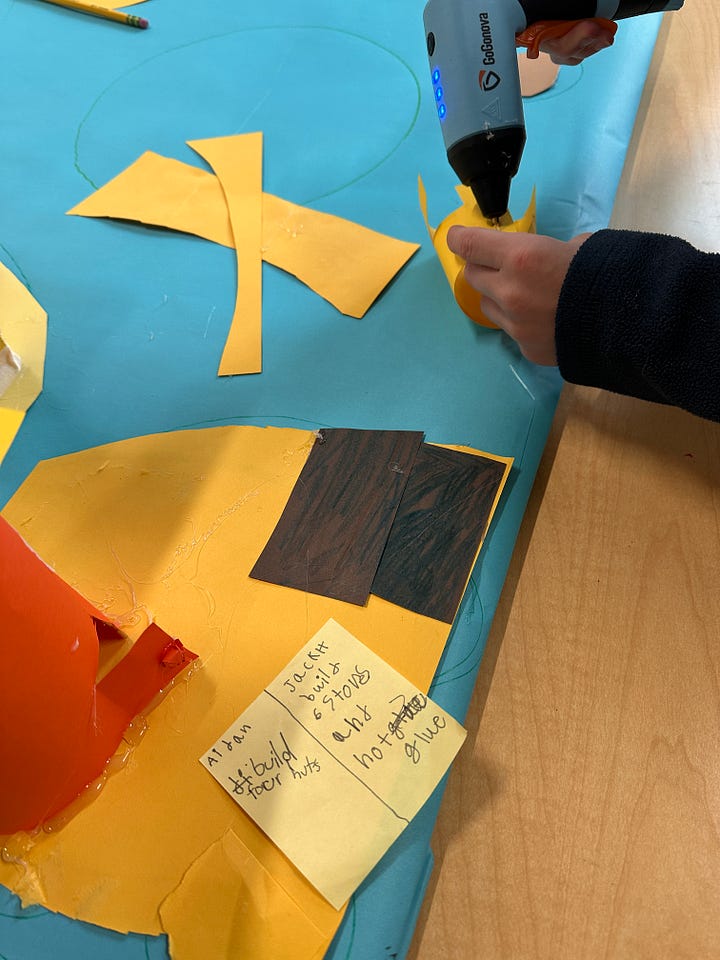

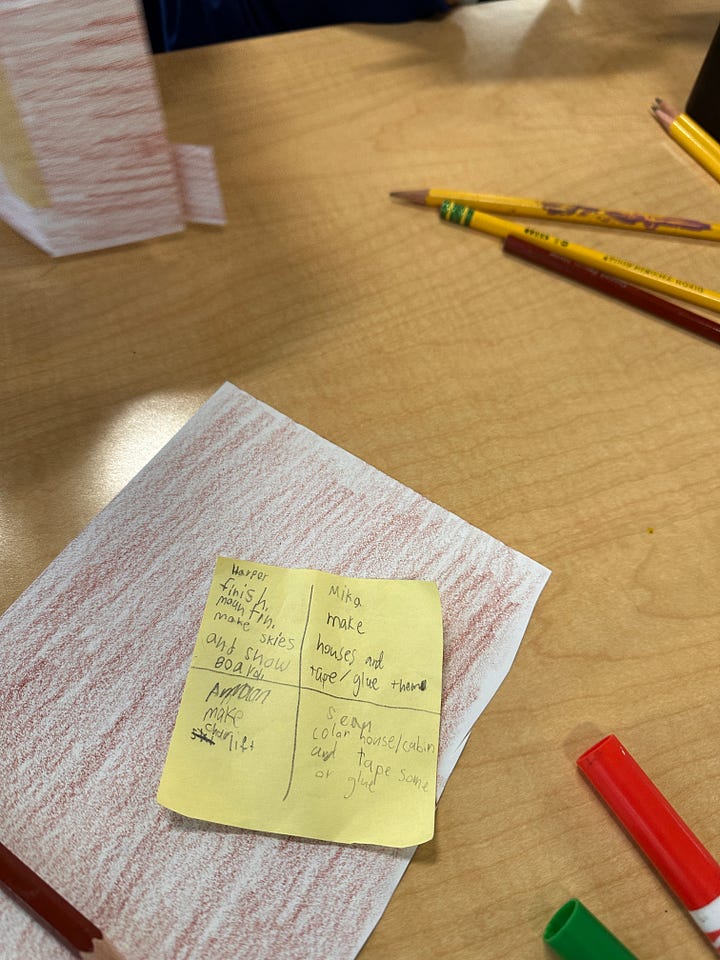

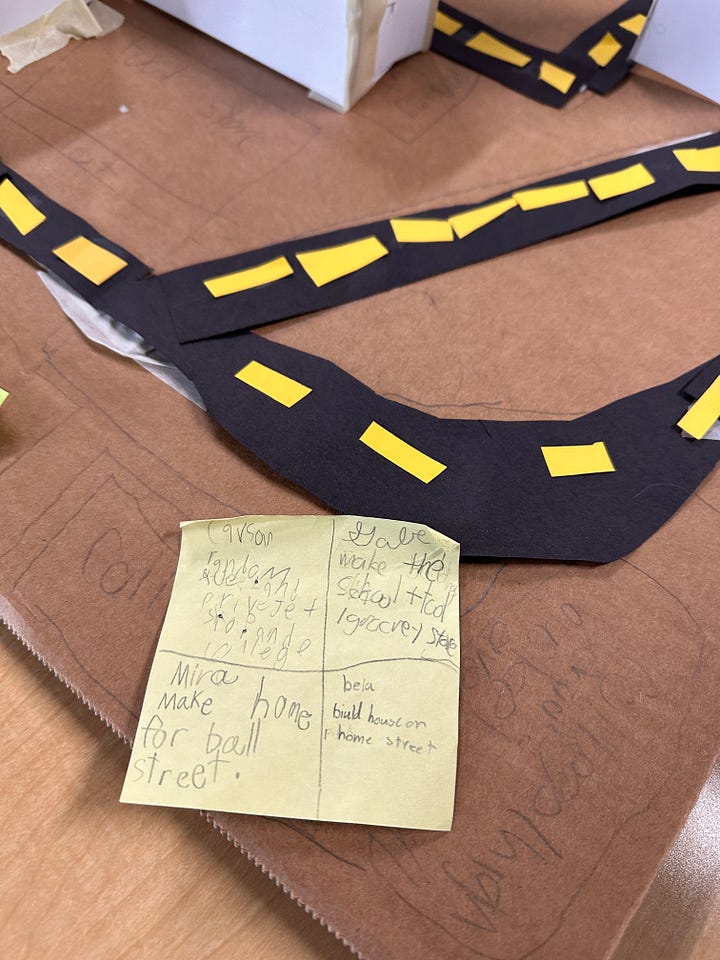

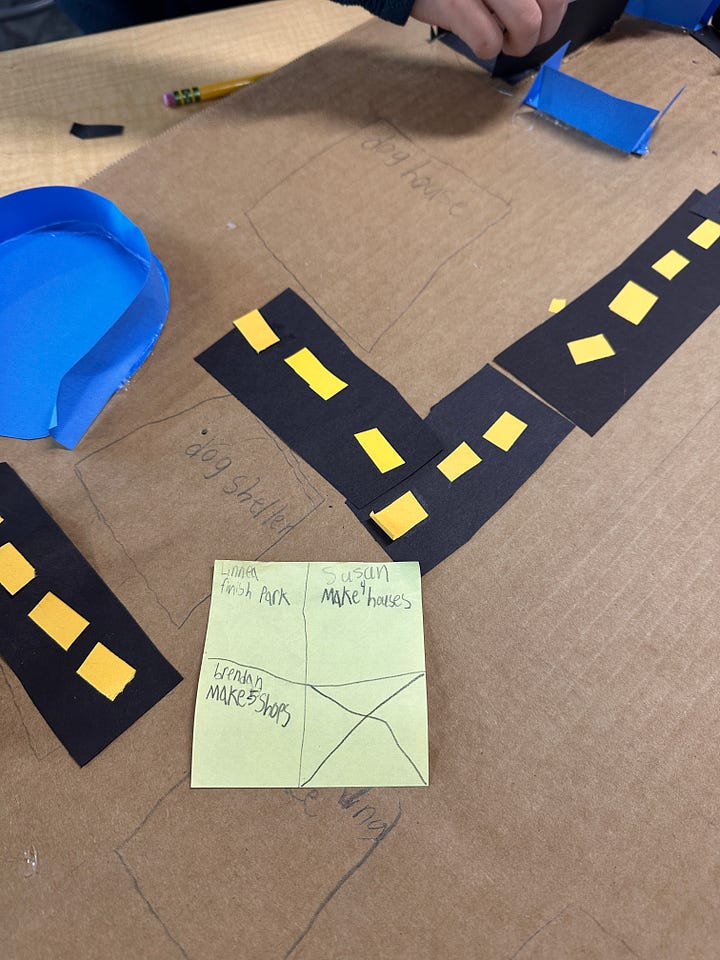

Let’s use one of my current 2nd grade classes as an example. They are currently engineering paper to create cardboard communities as a backdrop to their stop-motion animation film. They have nine, 45-minute class periods to complete this project before we move on. The project includes creating a fictional world and building structures that exemplify the theme of that world. This would range from “Snow Lumberjacks” to “Artist Communities” to “Beach”.

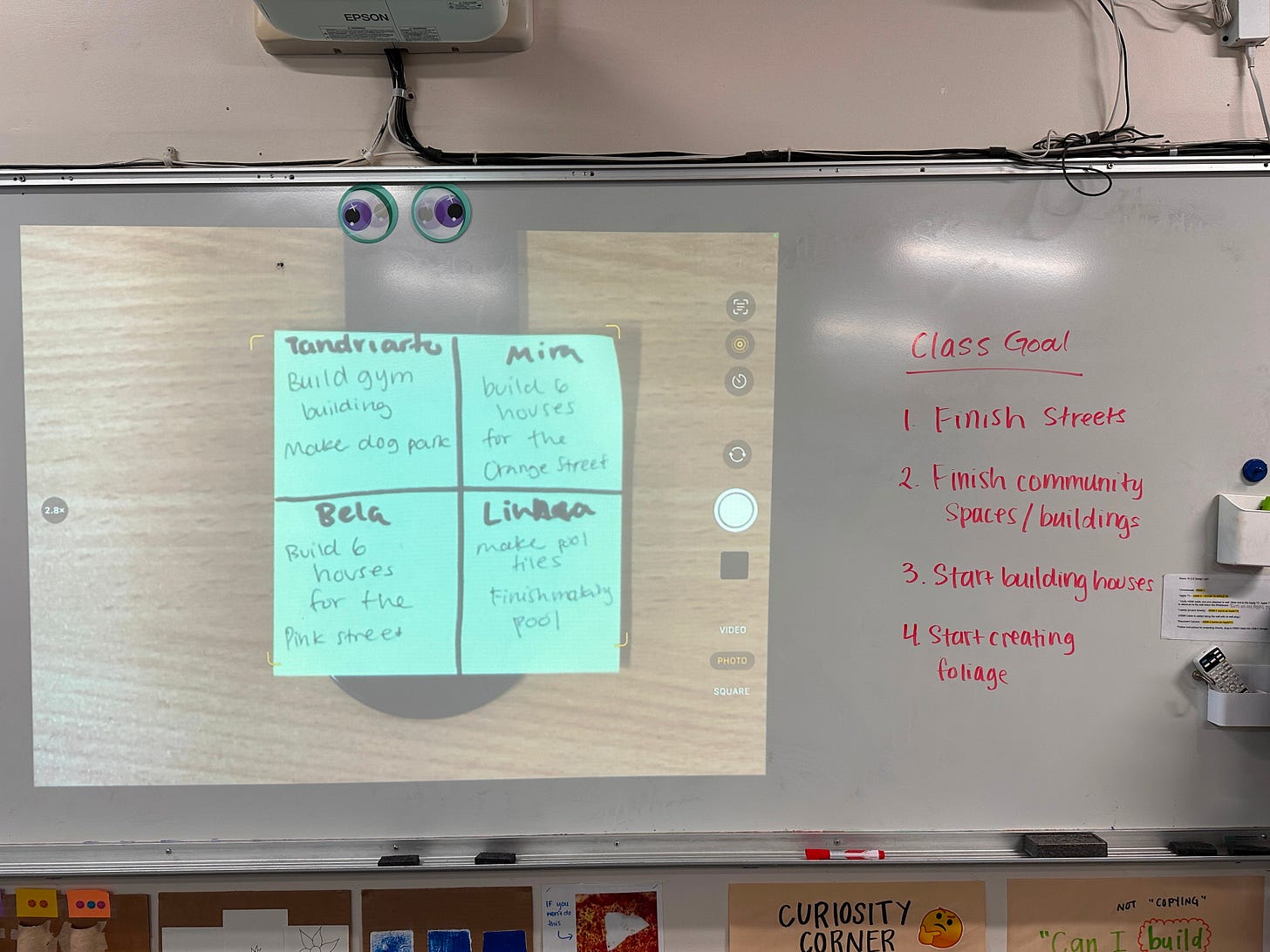

In the beginning of class, I would write down 3-4 goals that the class could choose to complete. These would be pre-determined as to expedite the goal-setting process. Out of those goals, students would start writing on their group’s Post-It with the following procedure:

Groups discuss which of the class goals they would tackle that day

One student would write down each of the members’ names

Each member would write down a goal they had for the class period

The goals had to be precise. Interestingly, I had a hard time defining “precision” to eight year-olds, but I eventually settled on a generalization that would rival United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous threshold: "You know your goal is precise enough when the goal doesn’t make sense to another group”.

Below are some examples of the ways that students use their Post-Its to keep members accountable:

Student Outcomes

In implementing this tool the last few years—and more recently within the last month—my observations are as followed:

Students themselves see a marked difference in their group efficiency. I had several second grade students come up to me, unprompted, and tell me that using the Post-Its made them feel productive and “get a lot more done than before”.

Students are holding each other accountable. There’s a level of detachment when students tell their group mates that they had agreed to a goal, rather than being perceived as “bossy”. When students are co-creating the goals and agreeing upon them, it’s not so much one leader telling the others what to do, it’s the Post-It.

Students are more engaged in their projects. Because students are taking ownership of their action steps and goals, they are more invested in the process of the project itself.

Looking Forward

The Post-It method has been extremely helpful for many projects, but I see areas for improvements in the future. This might not be applicable for every grade level, but each point could be used to modify the method to make it accessible and useful for your context.

Creating a “dock” to insert all of the post-its so students can see their growth or reassess goals. Students could keep all of their past goals on a sheet of paper to refer to it as needed. It could potentially improve students’ metacognition on goal-setting as they would have context for their progress.

Open up enough time in the class period to reflect on their goals and make some for the next session. In a perfect world, I’d have 2 extra minutes every class period for students to give me a recap of their compliance to their goal. I started implementing this idea briefly when students reset the classroom quickly. I’d have them give me a thumbs up or down depending on if they met their goal. One random spokesperson would speak on the behalf of each group to give an update.

Assigning “Project Managers” for each group to give more student agency. In retrospect, this feature would defeat the purpose of a collective, democratic effort. However, there might be cohorts that would benefit in a little more top-down management for cohesion.

I’m not feigning perfection, but I will say my groups have been more manageable. I can’t imagine organizing lessons without group work. The richness of students’ engagement, conversations, and in turn, learning, is unparalleled with the use of groups.

What do you think? Am I missing anything? What are you doing to make your groups more efficient and engaging?